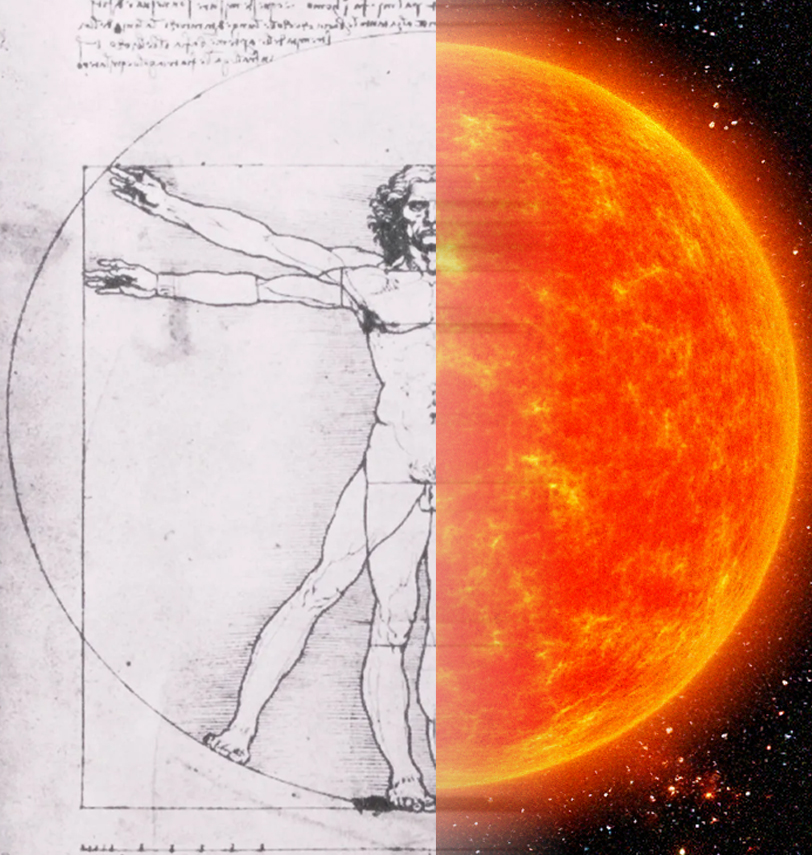

Even when there is a debate as to the exact moment, we can agree that there was a certain moment in ancient times, in which we can say that a certain species that walked the Earth became human. There is also a moment in the future, we can imagine, from which humans will no longer exist. In the vast timeline of the universe, then, the human species is limited to a small fraction. But is this species limited not only by time, but by space as well? In other words – is it possible that by wandering away from our home world, we will end up as non-humans?

Oren Ben-Yosef

I

Space… the final frontier. These are the voyages of the starship Enterprise. Her continuing mission: to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations. to boldly go where no one has gone before.

Jean-Luc Picard

It was 1996-7. We were in high school and gathered in a friend’s house, when one of my friends gathered the courage to say something that lurked there, in the back of our minds, while the rest of us were suppressing this dark notion. “The year 2000 is almost here”, he said, “and I don’t think there are going to be any mass-scale, civilian flights to other planets anytime soon…”. Laugh all you want, but for us, this was the dawn of a terrible realization. For years, we grew up on the sweetest fantasies of star-treking, hoping to get some of this sweet action in our lifetimes, meaning in our twenties. Sensing our worries, our friend then tried to offer some comfort, and said: “I am sure that the scientists will see that the 21st century is coming, and so they will invent something at the last minute”. To this day, no spaceship has taken me to other plantes. My friend was wrong.

In the universe of Star Trek, both the original series and in The Next Generation, we viewers are conditioned to see deep space as a comfortable expanse that is intelligently designed to harbor the rapid humanism of the galaxy. Not only are most habitable planets Earth-like, but most alien species are human-like as well. But these extraterrestrials were not only humanoid, all too humanoid, they were also a special kind of humanoid, meaning the kind that we no longer need. The Klingons and the Romulans resembled forgotten human empires, the Vulcan embraced a forsaken branch of philosophy and the comical Ferengi stood as an imaginary future statement about the human departure from greed. Every major nonhuman race was a ghost of human past, except for one specific alien race; a horrifying addition to the Star Trek universe, and if you watched The Next Generation like I did, you know exactly who I refer to.

Embodying the ultimate merging with technology, the Borg proved to be a terrifying encounter for the human crew of Starship Enterprise. This is a race that has reached the end of its history. It does not communicate, negotiate, explore, wonder or even go to war. All it does is move through space and swallow other races whole, for the sake of assimilating their technology and individuals into its collective. In its hive-controlled formation, the zombie-like Borg wander through space in cubical vessels, growing more and more invulnerable to exterior attacks, doing what is needed to be done in order to fulfill the only Borg directive: to make the entire galaxy, and then universe – Borg. Unlike other races, the Borg are truly alien, as they cannot be reasoned with, and they do not care for whatever petty habits other races have. This alienation lasts only two episodes. In the episode Q Who (Season 2, Episode 16) and in the double episode The Best of Both worlds (Season 3, episode 26 and Season 4, episode 1), the borg are indeed cybernetic monsters. In later episodes, they are defeated by whatever universal power that causes every alien race to become more and more human-like.

But the Borg did not only terrify us viewers. The even-more-scary aspect of their existence was that they were alluring. In one way or another, we all want to become Borg. This isn’t some goth-talk of someone who dreams about wearing cybergoth uniform all day long. In the last season of Picard, which aired decades after The Next Generation, this wish was actually fulfilled, when a human took over and became the new Borg queen. Star Trek is, ultimately, the realization of the dream about terraforming reality in its entirety. I’m a big fan of the show, don’t get me wrong, but yeah this is kinda strange.

II

“The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.”

H.P Lovecraft

Contrary to expansionist dreams and the human anticipation to devour the world(s) to satisfaction, the universe does not wait for us, nor does it care. In Eugen Thacker’s In the Dust of this Planet, the author points at a universe that is always there, haunting us while we struggle with the impossible attempt to understand it. There is the world for itself (Earth), Thacker writes, which is the world that we see, seemingly regardless of any human being. However, once we start thinking about it, or act to it, it becomes the world for us (World). This is where the universe of Star Trek is located. However, there is also the world without us (Planet), a world that was there before us and will be there after brief appearance on its surface. This is a world we cannot understand, as it is inherently an inhuman world. Not world (for us) or Earth (for itself), but a planet (without us) that operates on a cosmic level that is beyond our understanding. This is the perfect place to start talking about the demonic, and the corruption of the human into, well, into something else.

To Thacker, demonology deals with the inhuman and the incomprehensible, and as we will see soon enough, this may be the true destiny of space travel. I would add, without diminishing from the original claim, that the demonic, then, hijacks the human from its course in the world, changing the human trajectory and forcing it to orbit around the demonic. If we’re already in space, then you can celebrate Aleister Crowley’s famous claim, and imagine every man and woman as a star, and then imagine the demonic as a rogue black hole. In Star Trek, space travel has unified humanity, brought peace on Earth and ended our violent dependency on money. These are times in which humans are freed from the shackles of the need for survival and can truly fulfil their dreams. But then again, there is another really good TV series about space, in which the future is vastly different.

In The Expanse, space expansionism ends up very differently than in the universe of Star Trek. Not only that humans on Earth turn against humans on Mars, and vice versa, but more importantly – humans begin to become less human and more – something else. If you live on an asteroid, working most of your life without gravity, breathing artificial currents of air and living in eternal night, you end up as a new creature. If you use technology to augment your life in all possible ways, you end up as something else as well.

This is, in essence, the idea that stands behind Daniel Deudney’s mind-provoking claim, in his book Dark Skies. In his book, Deudney claims that successful space expansionism carries with it a real danger – the disintegration and disappearance of what we call human. Deudney mentions several dangers that will inevitably come with mass migration into different planets and celestial bodies in the solar system, including interplanetary wars, of course, and the weaponization of asteroids. But for me, two other dangers are much more relevant to the context of this article, in order to understand the existence of an inhuman power that negates the human. The first is species radiation, meaning the dissolution of mankind into several humanoid species with time, through natural evolution, through gene manipulation and through cyborgization. If you, for instance, imagine a human colony on collapsing Earth, another one on the moon, another one on Mars, and several others within the asteroid belt, giving each of them the time to adapt, biologically and technologically, to their own environmental conditions, you get very different alien races eventually. Next, imagine the political system through this kind of solar system – and it is going to be a system in which humans are not at all favored.

A second relevant danger, at which Deudney points, is the inevitability of off-world dictatorships, or in other words – states of unfreedom. Not only that as an interstellar pioneer, you may end up being enslaved to some powerful, super-rich entrepreneur who hires you for his off-world feudal base, but unfreedoms may also emerge in colonies that are created with the best of intentions. When trying to build a civilization in the harshest of conditions, with absolutely no room for mistakes, you can easily end up running a dictatorship – even for the sake of common good. Indeed, in this grim scenario, adventuring into outer space might confront mankind with the very essence of Thacker’s world-without-us, or with an inhuman agency, let’s call it that, that will leech on to us and drain us of humanity. Is outer space demonic, then?

III

A sufficient advanced civilization will have to surrender to the inescapable law of thermodynamic nemesis – the fact that no more can be put together than is being torn apart; from the inertial reference system of an accumulating economy, whose timeline runs from dismemberment to aggregation, any disaggregating force is an invader collapsing backwards from the future. It is this unsurprising that, as stated by Sitchin, ‘Marduk was coming into the solar system not in the system’s orbital direction (counterclockwise) but from the opposite direction. Nibiru, entering our world from the deep outside, is a planet forever in retrograde, because our sun-propelled gravitational time-loop prevents us from grasping the universe’s entropic drive towards destruction.

Gruppo di Nun, Revolutionary Demonology. 46.

In the Dust of this Planet is Thacker’s first book in his Horror of Philosophy trilogy. In the second book, Starry Speculative Corpse, Thacker writes about blackness and non-existence, in a way that can be then applied to this vast expanse of vacuum. We can now imagine space as a threshold, beyond which mankind ceases to be human, meaning that humans are indeed earthlings, while we live not only in a humanized world, not only on Earth, but also on a Planet, which is a part of a cosmological system that is beyond our understanding and beyond the limits and reaches of human thought. But when we examine the reasons, mentioned above, for the dissolution of freedom and the dissolution of mankind, we can attribute them not to the nothingness of space and the harsh conditions off-world, but to the technology that will be used in order to survive beyond our planet. The question, then, is whether it is space itself that is demonic, in the sense that it disintegrates the human, or is it this form of technology?

Like Luke discovering that Darth Vader is his father, we discover that yes – we are the children of our mother nature, but also of our father, technology. This can be seen in different way in which we change as a group, from a text-oriented society to an image- oriented society, as described in Neil Postman’s Amusing Ourselves to Death. Technology’s control over us is much more inherent.

In another Trilogy, Technics and Time, Bernard Stiegler relies on the research of André Leroi-Gourhan, arguing that technology and humanity co-evolve, with humanity shaping technology, which in turn is shaping humanity as well. Leroi-Gourhan saw technical invention as the principal characteristic of the human, even more defining than biology or culture. In Stiegler’s view, this means that there is no pre-technical human to which technics is merely an external addition. Instead, humanity begins with the first object, and so from the very origin of humanity, life has proceeded by means other than life. Human birth itself involved a fault of origin: Prometheus steals fire, Epimetheus forgets to give us inner protection, and we become permanently reliant on external (technical) tools. In this way, technics is co-constitutive of the human. It participates in anthropogenesis and defines our relation to time, memory, and self. We fantasize about children being raised by monkeys, wolves or other non-human animals, but it is us who are raised by the inhumanity of technology.

From here, we can also assume that, like the autorotative father who warns his son that “I brought you into this world, I can take you out of it”, technology does the same. It brought the human into existence, and once the human will use technology in order to live in deep space, technology will be the tool that will take humanity out of existence. Are we humans then doomed to be stranded on this planet, unless we decide to give away our very essence? Perhaps humans do belong to the world, while the planet demands the deterioration of such categorization. Perhaps we are to find out that humans have no place in deep space, and that only technology does. In the meanwhile, the nothingness of space draws us, calls us and pulls us into its inhuman bosom. “Come, my dears, come to me”, this siren is calling us. To be less human, to be more Borg, to stop being.